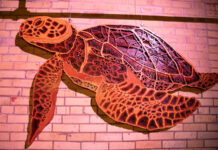

Tammie Rubin will make you see familiar objects in a completely new way.

Through her art, she transforms the ordinary into the fantastical. What you might initially recognize as a fishing net becomes a map or a web.

It’s up to you to decipher what her art means to you, as she provides a space for your imagination to run wild.

Tammie Rubin is this year’s winner of the fifth annual Tito’s Prize, facilitated by Big Medium and Tito’s Handmade Vodka. She’s an Associate Professor of Ceramics & Sculpture at St. Edward’s University, and a co-founder of Black Mountain Project, a new contemporary art platform in Austin.

I had the honor of delving deeper into Tammie’s practice as a sculptor, as she shared how her life influences her work and her advice for emerging artists.

I want to start out by asking, what brought you to sculpture as your medium of choice?

I’ve always been fascinated by three-dimensional objects and I credit that with a couple things.

I grew up in Chicago, and would take field trips to the Art Institute to look at the Armory room. They had all of these religious and sculptural objects that were in a vitrine, and a lot of them are very intricate and made of a variety of materials.

Also, being raised in the Lutheran church, I became very enamored with the ritualistic objects that would be used.

When I went to undergrad, I took a ceramics course, and then I took another and another.

The professor there had his studio attached to the ceramics facility and that was the first time I saw a working artist. I’m a first generation college student, so the idea of seeing someone practicing as an artist and also as an educator in higher education was really fascinating to me.

What is your thought process as you move through your creative work?

For me it’s more like looking at the slippage between what objects look like and what they resonate beyond their function. And how they have this resonance that is historic, or cultural, or social, or personal, and how they overlap.

When I’m in my studio there’s the research part, and then there’s the process-based part where I’m making molds, casting, mixing, building, and carving. So all of that becomes a way to convey the work.

Once the work is complete and it’s able to go into a space where I can share it with the public, that’s where I can stand back and see if things are having that sense of resonance with the audience. That’s what I’m hoping for, that they’ll have the same multiple associations with the work.

And a lot of times my work is on intimate scales so I want them to be lured in because the object looks familiar but you’re not sure what the context of the familiarity is, so now you have to get closer to investigate.

The surface becomes inviting but seductive and it’s very tactile. So you have this feeling of wanting to touch it or want more or to even understand what exactly it is.

“You should experiment, you should expand, you should not be afraid to fail.”

As a co-founder of Black Mountain Project, can you give us some insight as to how this project came to be and the role you hope for it to play in the art community?

Black Mountain Project is a three person project-based collective founded by Adrian Aguilera, Betelhem Makonnen and myself. We’re three individual artists of color who have different backgrounds, and our work is really different.

Our project has really been about things that we would like to see. Projects that we are engaged with that we want to do with other artists and collaborate with other spaces. So it’s about how to create expansive experiences with other artists, for other artists.

Does being a professor at St. Ed’s and essentially teaching your craft inform or influence your practice in any way?

It keeps me engaged in the contemporary art world.

I’m always making sure that I’m reading the theoretical things that are going to help me be a better professor with students and also thinking about their individual interests. It also keeps me authentic in the way that I’m telling the students, you should experiment, you should expand, you should not be afraid to fail. And when you say that to other people, you are also saying that to yourself.

So it keeps you honest in the studio to make sure that you are always striving for expansion and striving for ways to push my own artworks.

“I’m thinking about this show as a laboratory, to create a space of collaboration and conversation within it.”

How will the Tito’s Prize fund make an impact in expanding your practice?

Economically, it’s extremely helpful. Especially as a sculptor who needs equipment, space, storage, shipping, and all of those different things.

Also there are experiments that I want to do and this is going to give me the means to do those, and when the show comes together you’ll be able to see the outcome.

I’m really thinking about this show and this space as a laboratory and I’m hoping to create a space of collaboration and conversation within it. I think that’s part of the journey of this year, being able to have the resources to follow these wanderings that I’m thinking about.

What advice would you give to other artists looking to expand their practice and experiment in new ways?

I would say don’t be afraid. Also, talk with other artists, and after you do the talking, get to the doing.

I see that people will look at the video and do the reading but when it comes to actually practicing it themselves, they underestimate how much time it will take to become proficient at something new.

So it’s giving yourself enough time to fail and improve and keep experimenting forward, and not necessarily worrying about the immediate outcome from step one.

About the Author

Rhea Pirani is a multidisciplinary artist residing in Austin, TX. When she is not painting, drawing, embroidering, or dreaming about mountains, she enjoys engaging in conversations with other artists about their work, background, and creative process.